This blog post has been adapted from the introduction of my PhD thesis. I explored the contribution that photography and visual data can make to understandings of the mental health hospital environment, so first I looked at how photographs were talked about and understood by other scholars. I found that photographs have been conceptualised or used in 5 ways:

1. As pieces of evidence

2. As symbolic

3. As socially constructed

4. As springboards for debate and understanding

5. For political activism

1. Photographs as pieces of evidence

One of the most famous contributions to ‘realist’ theory on photography comes from Susan Sontag, for whom a photograph is an extension of, or surrogate for, its subject. In her 1977 book, On Photography, she draws a sharp distinction between ‘art’ and ‘photography’, arguing that whilst an easel painting represents or refers to a subject, photographs are part of the subject and allow us to predict, manipulate and decipher behaviour. This realist view takes as its starting point the assumption that the viewer is a rational subject undertaking a disinterested study of an (external) nature or society; Sontag separates information from experience, arguing that photographs provide an independent type of knowledge. She uses words like ‘report’, ‘coveted substitute’, ‘trace’ and ‘footprint’ to describe photographs, maintaining her view that photographs are “pieces of evidence in an ongoing biography or history”. We can see evidence of this realist perspective if we look at how photographs were used in the 19th and early 20th centuries. As part of the attempts to systematically document, categorise and understand the differences between humans, photographic archives of prisoners, asylum patients and deviants were collected. These archives were used to construct measures of normality whereby one’s ‘inner’ traits could be mapped by external features such as jaw angle or nose length. Photographs, in this example, were perceived to provide independent information regarding certain groups.

Case Study: Photographs of patients at Surrey County Lunatic Asylum

Dr Hugh Welch Diamond took photographs of patients in 1856 at Surrey County Lunatic Asylum. Diamond believed firmly in photography as a clinical aid to treating, understanding and representing mental illness. Backed by an article in the 1859 Lancet which described photography as the ‘art of truth’, this was indeed a popular discourse surrounding photography at the time, and was supported by psychiatrists who preferred the use of visual data to that of verbal description.

Case Study: Photographs as Data: An Analysis of Images from a Mental Hospital.

Authors: Dowdall, G.W. Golden, J.

Published: 1989

Journal: Qualitative Sociology. Vol 12, issue 2, pp. 183-213

This study explored institutional life in Buffalo State Hospital. Three hundred and forty-three photographs were sampled from a larger collection compiled from various sources including the hospital’s Director of Public Information, former staff members, annual reports, medical journals, newspaper archives, historical archives, book dealers and major photography collections. Whilst they acknowledge that the photographs are lacking in direct contextual support, the authors construct their photographs as unloaded reflections of reality. They draw a distinction between the photographs in their collection and ‘investigative photography’ which they say can be loaded with negative connotation. Instead, they compare their visual data with what they call ‘mental health photography’ i.e. media images of mental health, which they feel are “…literally snapshots of ‘the full round of life’”. In other words, the photographs are said to present an accurate and unbiased visual account of institutional life, an assumption that is highly problematic!

2. Photographs as symbolic

Whilst they remain an important contribution to photographic theory, Sontag’s essays offer little insight into the uses of photography in research as method or data. Roland Barthes, however, also seen by some as a realist, sheds some light on how this can be done. Barthes developed a specific and detailed method of visual semiotics in order to analyse photographic images. Barthes is concerned with two layers of meaning: the denotative (what/who is being depicted) and connotive (what ideas and values are being expressed and how). For him, the denotation of an image is simple and there is no need for a complex analysis; the photograph is merely depicting what was in front of the camera (in this way his view resonates with Sontag’s). Connotation, however, is a more complex level of meaning which looks at wider concepts and discourses being signified in the image.

Semiotics has been used in order to interpret photographs in mental health research, although the method has not been reported with much clarity.

Case Study: Facades of Suffering: Clients’ Photo-Stories about Mental Illness.

Authors: Sitvast, J.E., Abma, T.A. and Widdershoven, G.A.M.

Published: 2010

Journal: Archives of Psychiatric Nursing. Vol 24, issue 5, pp. 349 – 361.

This study from the Netherlands focused on the meaning of mental illness and suffering. The authors used semiotics to interpret photographs taken by service users. Each image was interrogated in terms of perspective, tone, setting, focus and themes. They then used Barthes’ approach to unravel the symbolic meaning of the image, understand this symbolism in relation to its context, and to provide information on the function this served for the participant.

3. Photographs as socially constructed

Some researchers adopt a social constructionist position and argue that all knowledge is contingent and there is no such thing as the ‘truth’. Researchers taking a social constructionist position within visual research highlight the importance of the motives of those behind the camera as well as other factors shaping photo-taking. Several studies that use photographs taken by research participants therefore include some form of narrative in order to give meaning to the images. The work of Gillian Rose is important here; she argues that although photography has been seen by many as a technology enabling us to record the way things really look, this is a construction of photographic meaning. Rose identifies three sites of meaning within images: production, image and audience. Constructions of photographic meaning have been influenced by structuralist and post-structuralist theory, including semiotics, discourse analysis and psychoanalysis. Rose offers a review of these approaches, discussing them in relation to issues such as what images do, how they are looked at and how they are embedded in wider culture.

Case study: Visualising a safe space: the perspective of people using mental health day services.

Authors: Bryant, W., Tibbs, A. and Clark, J.

Published: 2011

Journal: Disability & Society Vol. 26, issue 5, pp. 611-628.

In this study the researchers used participant-generated photography to look at the social environment of a mental health day centre. Photographs were constructed as illustrative of experience and the authors used the interplay between the photographs, the photographer and what was photographed to inform the analysis. In this way, Gillian Rose’s sites of meaning (production, image and audience) were examined to give the images meaning. Some photographs were metaphors, for example a photograph of a strawberry patch represented opportunities for self-help. The authors noted that most of the photographs required detailed explanations of their meaning, which points towards a social constructionist ontology of photographs.

4. Photographs as springboards for debate and understanding

Sometimes photography is used as a catalyst for discussion or to disrupt how certain issues are understood. Two ways ways in which this can happen are through photo-essays and photo-elicitation. Studies using photo-essays tend to be heavily focused upon the visual image as evocative or contemplative, aiming to capture attention from its audience. Photo-essays might be presented in an exhibition, online or as a book.

Case Study: Home at a Forensic Mental Health Unit: A photographic essay.

Authors: Heard, C. P., Tetzlaff, A., O’Brien, D., Borecki, R., Client ‘A’ (anonymized), Client ‘B’ (anonymized) and Client ‘C’ (anonymized).

Published: 2011

Journal: Photographies Volume 4, Issue 2, pp. 229-260.

This study involved service users and staff taking photographs of a forensic mental health hospital which were created into a black and white photo-essay. There was no narrative or words provided by the photographers about the photographs; the point of the photographs was to provide a visual context for “contemplative thought and discussion” of the lived environment of a forensic mental health service. The focus was on the field of reception (the audience) rather than the field of production (the photographers).

Whilst the focus for photo-essays is on contemplation and provocation, photo-elicitation is more about using photographs to stimulate discussion about a particular topic. Sometimes photographs are provided by the researcher, and other times participants take their own photographs. The images are then often used in individual interviews or in focus groups to elicit verbal data from participants. There is a growing body of theoretical and empirical literature relating to the use of images in this way. John Collier, Douglas Harper, Jon Prosser and Andrew Loxley are worth looking up for introductions to and examples of photo-elicitation.

Case Study: Images of recovery: a photo-elicitation study on the hospital ward

Authors: Radley, A. and Taylor, D.

Published: 2003

Journal: Qualitative Health Research. Vol 13, issue 1, pp. 77-99

This study involved giving cameras to patients on two wards (surgical and medical) in a hospital. Patients were asked to photograph 12 things that were significant about their stay in hospital. The photographs were then used in interviews where patients were asked to explain each photograph’s focus, and the memories and feelings each one evoked. This verbal data was then interpreted alongside the images during data analysis.

Roland Barthes provides some theoretical insights into how photographs can work to arouse contemplative thought or provoke discussion. In Camera Lucida (1981), his only works entirely devoted to photography, Barthes introduces two concepts – ‘studium’ and ‘punctum’ – to suggest ways in which photographs are interpreted. Studium refers to the interpretation of a photograph from a culturally informed standpoint. As Barthes explains:

The studium is that very wide field of unconcerned desire, of varied interest, of inconsequential taste … To recognise the studium is inevitably to encounter the photographer’s intentions, to enter into harmony with them, to approve or disapprove of them, but always to understand them … for culture (from which the studium derives) is a contract arrived at between creators and consumers.

Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida, 1981

In relation to photo-elicitation, studium can be seen as how people talk about photographs they have taken, or how they respond to photographs provided by researchers to elicit discussion. Barthes’ second concept is that of punctum, which he describes as a “sting, speck, cut, little hole”; a more emotional reaction to a photograph which escapes signifiers and is not able to be coded. The example Barthes gives is the repellent nature of Andy Warhol’s “spatulate” nails in a photograph by Duane Michals where he covers his face with his hands:

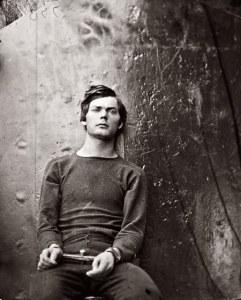

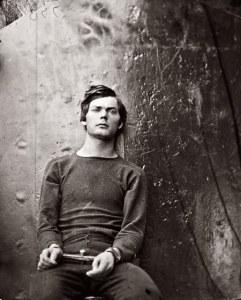

The feeling of repulsion that Barthes experiences when he looks at Warhol’s nails is nothing to do with understanding or an intellectual reading of the image, which would be the concern of the studium; it is a purely affective reaction to the image. Barthes also refers to the punctum of Time. For example, for Barthes the punctum of Alexander Gardner’s Portrait of Lewis Payne (1865), who was photographed whilst waiting to be hanged, lies in the simultaneous past and present tense of the image. In the photograph Payne’s death is imminent, yet in ‘real’ time he has already died. Barthes captioned the photograph “He is dead and he is going to die…”

5. Photography as political activism

Photography has been used in order to advance political agendas and to empower groups whose voices may not usually be heard. Photovoice is a technique used by health professionals and health promoters, as well as researchers, which is based on the idea that community education can empower people, creating ‘critical consciousness’. In Photovoice projects community members are encouraged to share their experiences in order to identify the structural, cultural and political conditions contributing to community concerns or problems. This method encourages community members to become ‘experts’ of their experiences and their local area, and aims to elicit responses from groups that may otherwise not be heard by policy makers. The purpose is to empower community members to address issues by identifying assets and inhibitors in the local area, or by identifying important people, places and events with photography. Related to this, several authors claim that Photovoice has the potential to engage participants in community matters when they usually would not be, again eliciting responses about the local community. This is done through community exhibitions or meetings, where local decision makers are invited to listen to the presentations of participants and view their photographs and stories.

Case Study: Flint Photovoice: Community Building Among Youths, Adults, and Policymakers

Authors: Wang, C., Morrel-Samuels, S., Hutchison, P., Bell, L. and Pestronck, R.L.

Published: 2004

Journal: American Journal of Public Health. Vol. 94, issue 6, pp. 911-913

This project, based in the town of Flint in Michgan, US, worked with youth groups, adult groups and policy makers. Participants were asked to take photographs of their community around issues they felt were important to them. Policy makers were involved to provide political will and support, but also participated in photo-taking. Participants chose their favourite photographs from those they had taken and wrote ‘freewrites’ to accompany them. The groups met discussed their photographs and freewrites together and identified common issues they felt strongly about as a group. These concerns were then shared with policymakers, community leaders and the media at invited forums, and the dialogue between community members and community leaders led to a number of material benefits for the community. These included a new Youth Violence Prevention Center and the renewal of funding for Genesee County Programs.

Researchers have used this technique with families and children, communities, youth, aboriginal women, breast cancer survivors, older adults, and people living with HIV/AIDS, but there are very few examples of Photovoice being used with mental health service users within the hospital environment. This may be due to the highly regulated nature of the mental health hospital environment. Although in part shaped by discourses of participation and public involvement, the mental health hospital remains an environment where institutional changes take place within bureaucratic, professionalised processes which service users may be involved in but that they do not lead. Opportunities for grass-roots political activism may therefore be less likely in this context than in other contexts.

In summary, there are a number of positions that can be taken when using photographs in research, depending on the questions being asked and the type of data that is collected. Photographs can be interpreted as pieces of evidence which reflect the ‘real’ world; as containing culturally significant signs or codes; as socially constructed pieces of data whose meaning is contingent upon a range of factors. Or, they can be used as a catalyst for contemplation, understanding and discussion of a topic, or for social action. I am sure there are also other ways that photographs can be theorised or used – have you used photographs in your own work and do you have a different perspective?